Thursday, April 9, 2009

I think Tong's article definitely goes under Feminism. The whole article describes the way third-wave feminism is taking a completely unique shape from the previous feminist movements. Tong categorizes first-wave feminism as the women's suffrage movement and second-wave feminism as being started and continued through the Civil Rights movement. Third-wave feminism however, is different because there is no real definition. Tong declares that "third-wave feminists are more than willing to accommodate diversity and change." She continues that "for third-wave feminists, difference is the way things are." This may be the stand third-wave feminists want to take but how can you take a stand for something that is not defined? I think one of the major problems for third-wave feminists is society's emphasis on being politically correct. If anyone wants a cause to become truly successful they must be careful not to offend anyone or any group of people. If people become offended the cause is most likely to go downhill fast because of all the bad press that will follow. For example, many people argued that the problem with earlier feminist movements was that they only applied to middle and upper-class white women. Particularly in the United States black women felt the so-called feminist cause did not relate to their needs or wants at all. Third-wave feminists in trying to combat and correct that problem have come to the solution that there is no exact definition of feminism and therefore women of all backgrounds can relate to and become a part of the movement. In my thinking this leaves a question for which I do not know the best solution. Is it more effective and productive to strictly or even at least loosely define the cause for which you stand in an effort to gain support of people who believe the same things you do? Or is it better not to define the reason for which you are trying to bring about change in hopes that more people will be enticed to join a cause that they can easily become a part of? I think this is the crossroads third-wave feminism has encountered and they are currently venturing down the path of the latter option. I guess only time will tell whether or not it is an effective decision.

Saturday, March 21, 2009

The Modern Woman

Abrams claims that the real impetus for First-Wave feminism was purely economic and political. I think she too strongly asserts this since each of these have more remote causes based in more fundamental areas such as culture, ideas and patterns of behavior. She actually seems to side with culture when later writing that "it was when 'the crust of patriarchy' began to crack from 1848 onwards" that organized feminism came about. Early feminists organized themselves through the release of statements (like the Quaker women's Declaration of Sentiment), political lobbying and protests. This process in turn assured greater women's rights as the women involved increased in oratory and written skill. They were successful in creating their own language and platform, from which they could activize on their own terms. Abrams also focuses on the relationship between socialism and First-Wave feminism, which was fruitful, but also split the feminist cause along class lines.

Masculinity in the British Empire

This chapter focuses on how conceptions of masculinity drove British imperialism in the period from 1880-1900. Professor Tosh asserts that "empire was man's business" in a literal sense. This is true in two ways. First, empire's "acquisition and control depended disproportionately on the energy and ruthlessness of me," and second, "its place in the popular imagination was mediated through literary and visual images which consistently emphasized positive male attributes." Since the chapter uses many examples of the effects of the man-making empire on labor patterns and also class considerations, I include this reading under the themes of gender, categories of difference (certain classes were more affected by the imperial propaganda program), and employment and work.

The author himself is not guilty of being caught up in the glorification of either empire or masculinity. He in fact seeks to undermine the role of increased masculinization by claiming that this last flourish of British ultra-masculinity was actually a symptom of weakness. While Britain--except between the years 1899-1902--was not at war during this period, they saw their international holdings as increasingly threatened by a hostile international environment. The saber-rattling and rhetoric about the need to defend the empire was therefore subsequent to fears about the instability of the empire.

I do not necessarily agree with Tosh on this point. The correlation of Britain's relative decline and increased masculine rhetoric is interesting, but it is difficult to establish causation here. During the allied bombings of Germany in WWII, German production in war materials actually doubled as the people became more resolved to survive, more angry, etc. For late 19th century British men, increased international competition from Germany, France and Belgium may well have initiated more "struggle, duty, action, will and 'character.'" Whether an increase in these traits results in greater masculinity is a matter of semantics.

Image: The Colonization of Africa. http://images.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://african-diaspora.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/05/colonial-africa.gif&imgrefurl=http://african-diaspora.com/2008/05/a-look-at-the-colonization-of-africa/&usg=__nivRd4Id-TxZ056hfPvJXwMa7Gc=&h=513&w=500&sz=51&hl=en&start=17&sig2=YAAqDGBNhy5x45tIG2UUmQ&tbnid=jJdUFX6pU0L0aM:&tbnh=131&tbnw=128&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dbritish%2Bcolonizer%26gbv%3D2%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DG&ei=LXLFSariIpK2sQOP1envBg

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

"Middle-Class" Domesticity Goes Public: Gender, Class, and Politics from Queen Caroline to Queen Victoria

Dror Wahrman traces the political treatment of the middle class of England through the decades of the 1820s and 1830s. As the title denotes, the main development he is tracing is the incorporation of women and the domestic into the political conception of the middle class. The brunt of his argument is found in one of the concluding sentences of the article which reads: “The picture of the ‘middle class’ as the epitome of hearth and home, in sum, should be viewed not as a straightforward snapshot of essential social practice but, rather, as a charged and contingent historical invention.”

Wahrman’s article opens on comparing two statements made by novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The first statement, contained in an 1831 essay, establishes a clear dichotomy between public and private, leaving public opinion to men and fashion to women. However, two years after that statement was published Bulwer-Lytton again discussed public opinion and fashion but did not divide relegate the categories to men and women respectively; rather, the categories were relegated to the middle class and aristocracy, respectively. Wahrman suggests that the difference in texts is not coincidental but reflects that the categories “middle class,” “public,” “private,” “masculine” and “feminine,” “invoked changing ranges of meanings and . . . carried different stakes at different moments.”

The trial of public opinion surrounding the episode of Queen Caroline in the 1820s asserted the opinion of the “middle class” was altogether male. The instance of women engaging in the public discourse surrounding Queen Caroline contained in the article was an address to the queen which was printed in the Examiner and the women are excessively meek in their writing saying at one point, “We are unaccustomed to public acts.” However, Caroline was considered “a woman’s cause” as “women acted as defenders of familial values and communal morality.” Nevertheless, at this time women were not considered part of the middle class voice speaking out against the injustice facing Caroline.

The rhetoric used to discuss the middle class changed with the passage of The Reform Bill of 1832, although there is some debate as to whether or not some social change on a longue duree level had not occurred earlier. Nonetheless, the middle class began to be associated with familial values, particularly with religious devotion and soberness, all which placed increased emphasis on the domestic—traditionally the woman’s realm. Wahrman evokes Joan Scott in his discussion quoting from her “Gender: A Useful Category of Analysis” the following phrase: “the concept of class in the nineteenth century relied on gender for its articulation.” Wahrman’s article and his tracing of notions of what defines middle classness reflects the validity of Scott’s statement.

Thematic Categories: Categories of Difference (Middle Class vs. Aristocracy—something I didn’t mention much, but very explicit in the discussion of Queen Caroline), Gender, Marriage and Family, Feminism (discussion of Mary Wollstonecraft, William Thompson, among other feminist writers)

Monday, March 16, 2009

1848 and European Feminism

This raises questions about why "the woman question" was perceived as so dangerous to mid-century governments.

Offen also asserts that women's participation in and impact upon 1848 has been "incompletely understood." She states that one reason for this might be because "it seemed too disruptive to historians preoccupied by a male-centered political agenda" (Offen, 109). That is a very provocative statement. With which historiogoraphic tradition is Offen conversing? What is she suggesting about the history of 19th century politics?

Image: Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830 (from Web Gallery of Art)

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

The Politics of Women's Work: The Paris Garment Trades 1750-1915

This association of women with low quality labor is complicated by Coffin's analysis of Dupin's ideas about woman's education. Dupin's theory was that women should be taught basic geometry and applied mechanics in a trade school because of the precision, regularity, and symmetry needed for women's industrial work. According to Dupin, since the female body was weak, the forces which they do possess must be cultivated and fully utilized, just as one would attempt to fully utilize any economic force. This thoery represents the types of questions about women and thier assorted capacities which the innovations and changes of the industrial era inspired.

Dupin goes on to discuss the developement of ready-made clothing and the subsequent immergence of departement stores; enterprises which marigalized the work of skilled tailors. These tailors added to the negative view of women during this period. As Dupin says, "as the tailors saw it, the decline of skills and ruinous competition were enseparable from feminization" because of the association, discussed earlier, of women with unskilled work.

Categories: Education, Employment, Gender

Sunday, March 8, 2009

Socialism, Feminism, and the Socialist Women's Movement from the French Revolution to World War II

Categories: Feminism, Categories of Difference, Citizenship, Labor.

Tuesday, March 3, 2009

From the Salon to the Schoolroom

Monday, March 2, 2009

Mary S. Hartman The Household and the Making of History (Cambridge, 2004), 242

Hartman suggests that the northwest European marriage pattern set up an entirely unique gender and family dynamic that in turn created the path of western history. Do you agree? Does Hartman's explanation for patriarchy and early modern gender also explain some of our contemporary attitudes about masculinity and femininity?

Hartman suggests that the northwest European marriage pattern set up an entirely unique gender and family dynamic that in turn created the path of western history. Do you agree? Does Hartman's explanation for patriarchy and early modern gender also explain some of our contemporary attitudes about masculinity and femininity?

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Reclaiming the Enlightenment for Feminism & Challenging Masculine Aristocracy

Overall I believe this reading fits under many categories, such as Gender, Employment and Work, Marriage and Family, Law, Education, and Citizenship, and because is was largely based in France and not spread until later times, Categories of Differene in region.

Saturday, February 21, 2009

Freedom of the Heart: Men and Women Critique Marriage

Another interesting aspect of this article is its focus on the written word. When contrasted to last week’s readings “The Perils of Eloquence,” which suggested that women were losing influence because print was replacing oral , Desan presents several examples of women who were writing eloquently. There were multiple pamphlets Desane sighted that were attributed to women. This seems to contradict Hesse’s assertion by suggesting that women maintained their influence by adapting to the written word. Although, Desan suggests that male authors could have written under female names, this still does not undermine the female influence since the male authors would not choose a female pseudonym if it did not provide more credibility to their work.

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

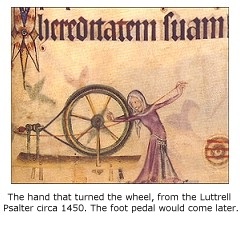

Spinning Out Capital: Women's Work in Preindustrial Europe, 1350-1750

Another thing that was discussed was the difference between where the men and the woman made their objects that they sold. Men were able to carry out their work in workshops where women had to make their items in the domestic area. This really stopped women from being able to do many of the types of work that men were able to do even if they did know how to do things like shoemaking, etc. Merry Wiesner talked about how even widows who would continue to do the work of their husband did not have the same advantages of their competition. The men that were doing these same tasks had the opportunity to get newer equipment that would help them, but women could not have these same things because they had to continue to make their items in the domestic area. The only occupation that was truly looked at as noble for women was becoming a midwife. This changed though when men started to go to school to becom physicians. They made different types of reasoning of why women should be pushed out of the job of midwifery and they should let men take over. Women were never given the opportunity to learn the same things that the males were able to. Merry Wiesner believed that these things happened because men thought that they would give women to much power if they were allowed to do the same work that men were allowed to do.

Carla Hesse: "The Perils of Eloquence"

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Having Her Own Smoke

This article outlines several of the most common employment opportunities available to singlewomen in Germany from 1400-1750. For this reason, I've placed this article in "Categories of Difference". Wiesner analyzes, specifically, Germany in a comparatively short span of time - these demographics anywhere else at any other time could very well have yielded completely different results.

In addition, Wiesner discusses the lifestyle differences between the employment opportunities. She describes the characteristics of singlewomen who were domestic servants, wage laborers, and those who participated in craft production and sales. While each of these lifestyles resulted in different freedoms and certain restraints for singlewomen, they were all held suspect in terms of their motivations for being single working women. Working women were subject to the stigma of being associated with lewdness and, in some cases, prostitution.

~Melissa Johnson

Sunday, February 8, 2009

Women in Early Modern Europe

In many ways the women of European colonies had more rights and opportunities then their European counterparts. However just as in any situations, there were some things that were better for European women. Within the article it is apparent that we can see Categories of Difference within the women from all over the colonies and all over Europe. Marriage and Family plays a role in the different marriage ages we see in Europe and the colonies and the different sizes in families. Employment and Work become important as women in the colonies tended to have more job opportunities available to them. Lastly, Law, Education and Citizenship can be seen in the role women played in all of these communities, as education became important and women were able to access legal help in some of the colonies like those of England.

Friday, February 6, 2009

Would you rather live in Salem or Montaillou?

Reasons for choosing Salem:

Respect (mentioned three times)

Responsibility (mentioned three times) Overall quality of life for women (mentioned twice) Just legal system (mentioned twice) Lack of pressure to marry “someone extremely older than you” (mentioned twice)

More overlap with men and women’s roles (mentioned twice)

More power in daily life (mentioned twice)

Because women had it “a little easier than Montaillou” More equality (less machismo)

And then these quotes that neatly summarize the ambiguity of preferring Salem:

- “In Salem the men more readily admitted their fears of women gaining social power”

“I wouldn’t have wanted to live there [Salem] then, but before [the trials], I’d want to live in Salem. Probably.” - “Even though my chances of being raped, accused of witchcraft, and becoming a “spinster” would be greater, I would have more freedom in choice of work, gender roles would be less defined, and since women would outnumber men, it would be more acceptable for me to choose not to get married than it would be in Montaillou. (Where I probably wouldn’t have a choice.)"

- “Despite Salem being more dangerous as far as the propensity to be a victim of violent assault, I feel Salem is more akin to the world I am acclimatized to. Today women aren’t considered witches and executed, but something that rhymes with witches and are sacrificed on the altar of public opinion.”

Reasons for choosing Montaillou:

- “Who’s to say that the women didn’t retaliate with equally derogatory remarks that were not recorded?”

- “Even though, perhaps, women on the whole were less revered than in Salem and more openly scorned they also had more autonomy in their own sphere”

Davis, "Arguing with God"

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

Reading: January 28, 2009; The Burdens of Sister Margaret

This reading, quite obviously, deals with the theme of religion. It recounts the life of a nun in early 17th century, showing the reader how life was for a nun at the time. It sheds light on the relationship that existed between women, religion, and witchcraft. At the time it was believed that women were more extreme, and therefore more likely to either be very good (devout nuns) or very bad (witches). In fact 80% of the people charged with witchcraft between 1500-1700 were women. We also learn that people believed there to be a connection between sinful acts welcome in evil spirits and possessions.

Another theme of this reading is categories of difference. There are some facts and statistics mentioned that deal with other locations, but almost entirely, the perspective given is one from the Low Countries (Netherlands).

Sunday, January 25, 2009

'The Reformation of Women' Chp. 7 of "Becoming Visible"

In many ways, Karant-Nunn's work parallels Joan Kelly's article, 'Did women have a Renaissance?' Both the Reformation and the Renaissance which seem to provide greater progress for humankind have the opposite affect on women. Karant-Nunn relates how before the Reformation, women were members of confraternities, nuns and healers. She also claims women were allowed some part in feast days, processions and the commissioning of art. Karant-Nunn argues that the Protestants stripped women of such inclusion, focusing more on the role of women as wives and mothers. Many convents were closed, forcing women without skills back into a world they were ill prepared for. Protestant reasoning said that all people had lustful desires and that marriage was ideal to keep such in check and propagate the next generation of Christian believers. Because Protestantism could only survive in state-sponsored environments, both the church and state worked to reign in institutions that supported single women, namely convents and brothels. The Protestant attitude,Karant-Nunn asserts was even more hostile to women than before because it rejected the iconography and worship of the Virgin Mary which provided another woman aside from Eve for women to become associated with.

The Counter-Reformation sought to impose uniformity, which Karant-Nunn argues, led to the narrowing of religious scope for women. Though convents remained an option for women, the movement of nuns into the secular world was much more limited and essentially they were confined within the walls of the convent and more heavily regulated than before.

The final piece Karant-Nunn discusses is the witch craze. She says that without the compliance of theologians, judges, lawyers and magistrates, the with craze never would have occurred; essentially the world view of all these educated men was steeped in religiosity that allowed for the hunting of witches. The witch hunting was associated with females and included treatises written about women and witches and sexual overtones which all reveal in Karant-Nunn's opinion how the anxiety over church and state caused by the Reformations revealed the misogynistic attitudes of the society.

-Deborah Goodwin

Tuesday, January 20, 2009

Notes on "The Dominion of Gender of How Women Fared in the High Middle Ages" by Susan Mosher Stuard

Stuard also uses a number of other themes to organize her arguments. She relies heavily on changing marriage dowries (marriage/family; economics) and the male clergy's interpretation of Christian doctrine (religion) and classic Aristotelian dogma to explain why women slowly lost rights to govern, make laws, and receive education (citizenship and law; education). Ultimately, the progress that men experienced in these centuries resulted in the loss of rights for women as they were given the negatives of attributes assigned to men. These developments are still impacting our society today, making the modern women's movements necessities for achieving equality (feminism).

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

Recap of the readings for January 14th

1. I think that Elaine Sciolino's article can fall under Law, Education & Citizenship and Employment & Work. It works in both of these categories because of the emphasis on women's roles in politics both in the past and currently in France. Another category that would work would be Feminism. It is argued in the article that Royal emphasizes both feminine and feminist traits to win over the voting public.

2. Bonnie Erbe's article goes well in the Gender category because it discusses how the roles of men and women are changing in regards to working in the business world and at home. This article also fits under Categories of Difference because it seems that the sample of people discussed were only couples living in urban areas.

3. The Family: A Proclamation to the World goes well in the category of Gender. Throughout the document men and women are referred to in equal terms. though some roles are specifically mentioned for each sex there are no specific limitations put on being able to also participate in other roles as part of a couple or as a parent. Obviously this also goes under Marriage & Family because it discusses both in combination between husband and wife and also in regards to separate responsibilities of each.

4. Categories of Difference is a good fit for Robert Ebert's article because it discusses the way class and age differences between Queen Elizabeth and Sir Walter Raleigh were ignored or smoothed over in the movie. It also works in Feminism in that the movie seems to take a woman who was in charge of the country and downplays that role to the point that the focus on her is the romantic aspect of her life which in reality did not even exist.

5. Robin Abcarian's article on the public's reaction to Sarah Palin as a Vice Presidential Candidate could be put into the category of Feminism because the article mentions how Palin is representing a new type of feminist. A conservative feminist. Also, the article goes well with Marriage & Family because it discusses how Palin's family represents a sort of opposite of the traditional American household. Palin is a mother of 5 who has a very demanding career but whose husband is extremely supportive of it. That idea is different and still somewhat new to many people in the world today.

Saturday, January 10, 2009

Gender: An Overview of Monday's Reading

As for the second piece of reading it also falls under the theme of gender. In Joan Kelly's work she uses gender or the differing ideals of men and women, as well as the differences in their power during the Medieval period and that of the Renaissance period, to show that unlike most men the Renaissance for women actually meant a decrease in power and another shift in gender relations. To some the piece could more directly be placed under the theme of marriage and family because of Kelly's emphasis. But that is only part of the whole picture, because Kelly uses marriage, family, the courtly love of the medieval period, and ladies of the court in the Renaissance to show the shift in even the minor power that was granted women in the medieval period to that of their husbands.

Thursday, January 8, 2009

Welcome to History 318 - European Women's History Since 1400